Readers, this post is picture-heavy and thus too long for email. To read it in its entirety, you may have to go to the website or the Substack app.

Thoughts of mid-20th century dinner parties stir up images – and sometimes memories – of vile-looking dishes, at least to our modern sensibilities, of lettuce, or worse, fish, encapsulated in clear gelatin concoctions. Jellied hamburger loaves. Leftover salad with celery, cheese, and stuffed olives that stare like bloodshot eyes straight into your soul through the clear green lens of lime gelatin. These and other similar monstrosities are often brought up as examples of how terrible food used to be. And it is perhaps because of dishes like these that the popularity of gelatin has fallen in the US, but these curiosities are not even remotely the most interesting parts of the history of gelatin in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Most of these dishes we have come to feel so much disdain for were made with JELL-O, a flavored and sweetened gelatin powder. But Knox, the brand that makes unflavored gelatin that also partook in the aspics and jelly salads, has a much more interesting history. And yet, we rarely hear about it.

Humans have used gelatin for hundreds of years at least. Aspics, that is, savory jellies, of all sorts appear in cooking-related sources as far back as the 10th century CE. That is the consensus, anyway, that gelatin’s use as we know it to thicken liquids and encase other foods dates to this time and first appeared in Kitab al-Tabikh, or The Book of Dishes, hailing from Baghdad. It now appears in a few translations, the most popular being A Baghdad Cookery Book by Charles Perry. In Kitab al-Tabikh, the gelatin is made by boiling fish bones and fish heads.

But there is an even older cooking manuscript that mentions gelatin preparation. Apicius de re Coquinaria, compiled in the 5th century CE or before, contains a recipe called “salacattabia Apiciana,” or Apician jelly, numbered 126. It is a molded mélange of ingredients like chicken, calf sweetbreads, cheese, vegetables and more, flooded with jellied broth. The mold was then buried in snow to solidify. The whole thing was unmolded, sprinkled with a dressing, and served. This is an aspic, without a doubt. By the 19th century, jellies, aspics, and other gelatin concoctions were extremely popular with the wealthy. It is the Victorian era, and not the mid-20th century that gives us the most spectacular molded gelatin creations.

But obtaining this gelatin was nasty work. During the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period, gelatin was obtained by boiling cow and pig hooves for hours. The resulting stock was passed through a cloth bag to strain it, boiled once more, and finally allowed to cool and solidify. It was a smelly and unpleasant process. In 1681, Denis Papin improved this process through the development of a new method that extracted gelatin from bones rather than hooves. In 1812 Jean Pierre Joseph d'Arcet improved the process once again by introducing the use of hydrochloric acid combined with steam. Still, making gelatin wasn’t a pleasant experience at home, where the older ways were still the norm.

Then Knox came along. Charles Knox developed granulated gelatin, the story goes, after years of watching his wife go through the tedious and unsavory process of making gelatin. At first, Knox hired peddlers to teach women how to use his gelatin and, of course, to sell it. This was in 1894, and in 1896 Rose Knox, the wife, going by Rose Markward, published a booklet called Dainty Desserts for Dainty People with recipes on how to use the gelatin. Prior to being sold in granules, Knox’s gelatin was sold in shredded form from 1891 through 1893.

Riding the coattails of Knox, Pearl B. Wait, a former cough syrup manufacturer, developed JELL-O in 1897, which they sold to Orator Francis Woodward in 1899. It wasn’t initially popular, but it would later become popular enough to worry Knox.

The difference between Knox Gelatine and JELL-O was, and still is, that Knox was just gelatin while JELL-O was flavored and mostly sugar. This fact would become the main point of differentiation between the two, and what the Knox company uses until now to differentiate themselves. Knox condemned JELL-O as unhealthy and their own product as the epitome of health. In this pursuit lies the strange history of Knox Gelatine as baby food, health aid, weight loss supplement, and much more – a pursuit that remains active to this day.

Initially, the ads for Knox products emphasized the pureness of the gelatin and the ease of use. In Dainty Desserts for Dainty People, for example, they claim that Knox’s Sparkling Calves Foot Gelatine, “the purest made,” was recognized as “the Standard by all users of pure food.” They go on to explain that “you have, no doubt, noticed, while pouring the hot water on some gelatines, a sickening odor which will arise from it (this never will happen in pure gelatines), and shows that the stock is not pure, so is unfit for food.” Anyone who has used granulated unflavored gelatin today, a niche that Knox effectively monopolizes, will no doubt, to borrow, Knox’s own words, have noticed that sickening smell, casting the shadow of doubt over Knox’s claims.

The cultural context of when Knox came onto the scene explains their emphasis on the pure food rhetoric. The end of the 19th century was the height of the pure food movement, a reaction to the increasing physical and metaphorical separation between producers of food and consumers of foods. Railways, refrigerated cars, industrialization, the rise of large national corporations, and other changes during the century meant that people began to grow suspicious of food grown by anonymous producers and packed by anonymous packers far from where consumers lived. To be sure, fears over the adulteration of food are as old as humanity itself, but this period was a turning point.

The first mass calling for government regulation of food and drugs began in the 1880s, and, unsurprisingly, women were at the core of the movement. This was especially the case when it came to drugs and alcohol, but food as well. The government didn’t really respond until thirteen children died in 1901 from a tainted diphtheria vaccine. Congress passed the Biologics Control Act in 1902, and shortly after allocated money for the research of preservatives in food and their impact on those who consumed it. All of this led to the passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Federal Meat Inspection Act in 1906.

Knox Gelatine, whose main target audience was women – largely responsible for both feeding and for the well-being of their families – leaned heavily into these calls for pureness to promote their product. As JELL-O’s popularity grew, Knox leaned more and more into the health and medicine rhetoric, as they positioned themselves as the opposite of JELL-O. This change began under the oversight of a woman, Rose Knox, who ran Knox Gelatine Factory from 1908 when her husband died.

While an early 20th century advertisement shows a baby thinking “just wait till I get a little bigger” while staring at a molded jelly, the message quickly changed.

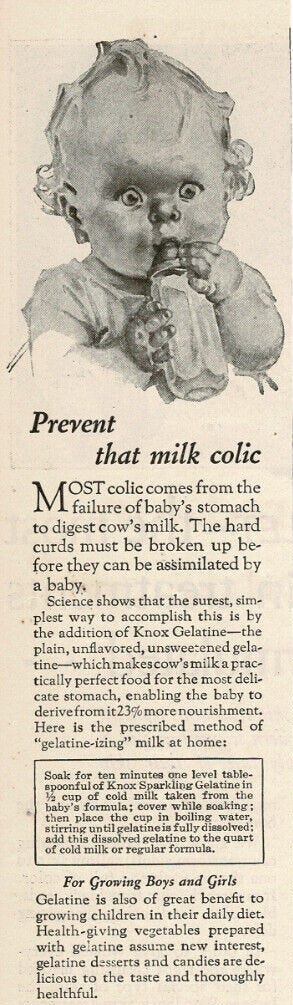

One of the earliest approaches to Knox Gelatine as more than dessert or treats made with a pure product was to promote the product as a baby food and baby health aid. A 1924 ad claimed that Knox Gelatine could help babies digest cow’s milk better. Knox Gelatine, according to the ad, helped babies’ stomachs break down the milk curds for better digestion, saving them from malnourishment. Older children could benefit too; parents could get sneaky and disguise vegetables in gelatin.

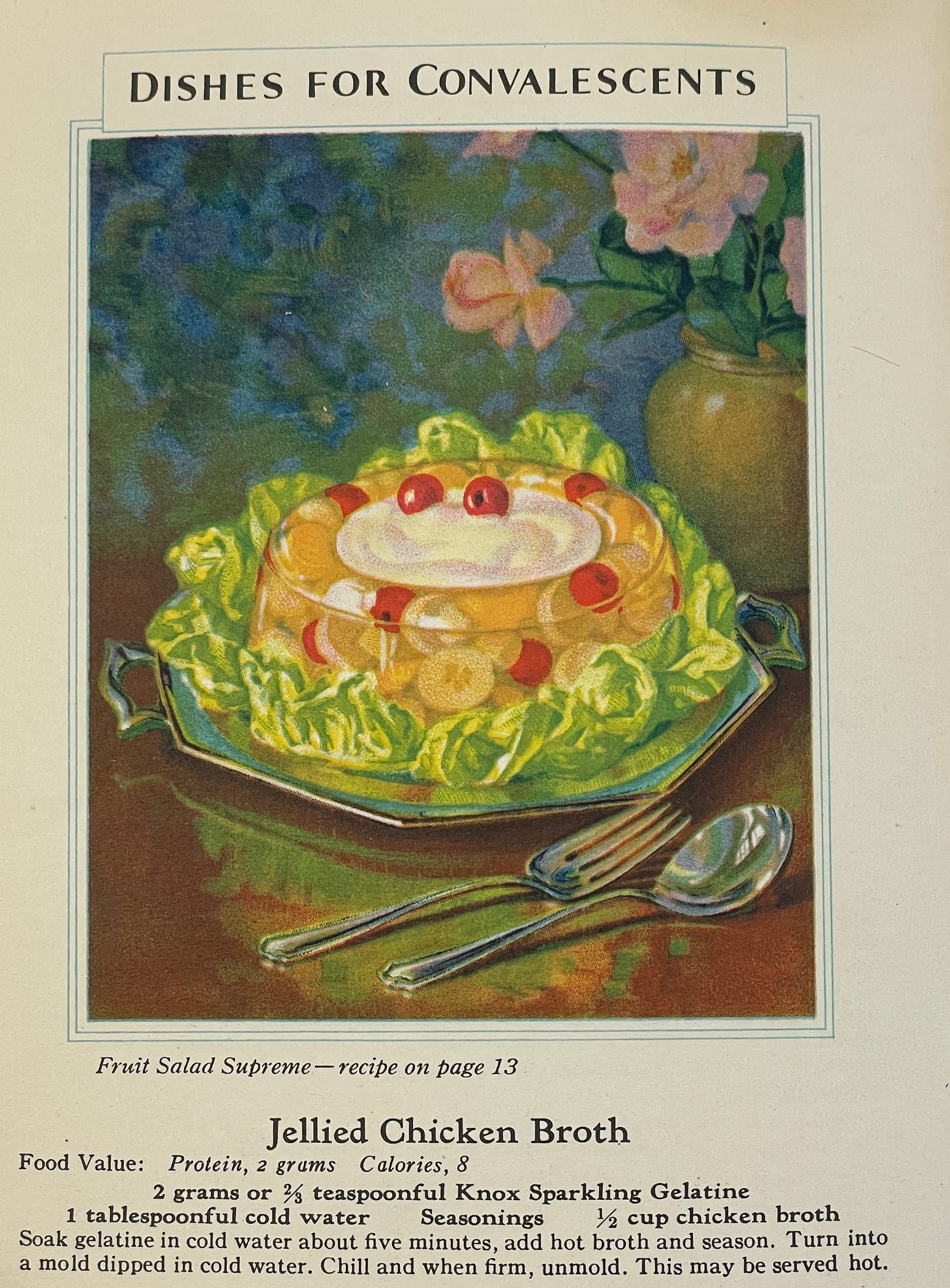

By the 1930s, the whole family could benefit from Knox Gelatine’s purported health properties. Fatigued or tired? A “scientific discovery” showed drinking Knox could help. Convalescing? Knox was there for you! Need stronger nails? You guessed it, Knox! Peptic ulcer? Knox gelatin was the therapy.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, Knox advertised in nursing journals promoting the gelatin to the medical community as an aid for all sorts of ailments. They particularly promoted it for special diets like those low in calories, high on protein, or bland diets. Patients needing to supplement their protein intake could mix Knox Gelatine into water, juice, or milk for a digestible boost of protein. If patients were on a low sodium diet, well, Knox Gelatine was low on sodium. Geriatric patients could benefit from Knox Gelatine’s “ease of digestion, and its easiness on dentures.” If hemoglobin formation was the concern, “Knox Gelatine contains important glycine and proline necessary” for the task. As far as Knox was concerned, their gelatin could be used for just about anything health-related. But you should never, under any circumstance, confuse it with “ready-flavored gelatine dessert powders which contain about 7/8 sugar and only about 1/8 gelatine.”

Despite their attempt to target healthcare providers directly through advertising in these journals, there was one type of diet for which Knox went straight to the end user, and their longtime target customers: women. The diet was dieting itself, or reducing, as it was commonly called at the time. Knox promised women that their product would not just help them lose weight and keep it off, but that it would make the process a pleasure. In the 1939 booklet “Be Fit Not Fat,” a woman in a big hat, white gloves, and extraordinarily high heels stands on a scale while looking at the number in horror. We, the reader, can see that she is rather slim, and her puppy is also standing partially on the scale, increasing the offensive number.

This booklet “contains a carefully selected list of delectable desserts and salad recipes especially designed to make dieting a pleasure for weight-watchers.” The idea was to lighten up these courses, to substitute them with options with fewer calories, so women could satisfy their sweet tooth without the “silhouette-wrecking” effects adding more calories to their diet might cause. By the 1950s, these substitutions had morphed into an entire dieting plan, dictating what to have for every meal of the day.

The “Eat-And-Reduce” plan, as Knox called it, according to them, helped “thousands of overweight people to gain a slimmer, more youthful, pleasing figure.” The argument for gelatin’s role in the success of the diet was that, since the gelatin was all protein and no extra calories, it could make people feel less hungry while eating less. Each day had five meals: breakfast, mid-morning quick-up, lunch, mid-afternoon quick-up, and dinner. For each meal, along with other foods, dieters were to drink Knox Gelatine in either juice, bouillon, or water, and more gelatin was cooked into various dishes. Depending on the day, the total number of calories was between 1235 and 1374 with no differentiation for age, height, activity level, or anything else.

Not all the health claims that Knox has made during its strange and ever-adapting career are necessarily wrong, but it is painfully obvious that every single one was an attempt to differentiate themselves from the ever-popular JELL-O. Knox chose to go the health route in marketing their gelatin in direct opposition to JELL-O, whose approach was entirely based on the pleasure and “joys” of eating dessert with all the sugar and all the calories; concern for diets, ulcers, or fingernails not welcomed. Even today, Knox positions itself in the same way, despite the fundamentally different natures of the products.

“Knox Unflavored Gelatine is as timely as ever,” their website says, “as a low-calorie, pure protein food, it fits perfectly into modern lifestyles as an essential ingredient for light, healthful cooking.” You can even use it as “Golden Scrubbing Grains” for your face for all skin types. Just mix equal parts by volume cornmeal and Knox Gelatine, dampen your face, scrub with the mixture, and rinse.

My older sister and I traipsed through my mom's old battered recipe folder together recently and had a laugh over ALL the recipes with gelatin in them. Mom was among those looking to keep her fingernails nice and strong thanks to all that Knox!

Rivetting piece, as always.