Origin Story

Pop culture villains have origin stories, and food historians do too. This is mine.

First of all, I want to thank every single one of you who subscribed to this Substack sight unseen, before you ever read a single post. Thank you from the bottom of my heart, or maybe my stomach, which is bigger.

You can also find me on Instagram, Twitter, and Mastodon.

The Story

I spent quite a bit of time trying to decide what the first post in this publication should be. Should it be a recipe? Should it be something related to why we study food? Maybe some esoteric writing on recipes? The possibilities were endless. In the end though, I settled on telling you how and why I became interested in culinary history and in food in history, and later an academic [food] historian. Yes, I do have the audacity to believe you care.

It all started at the tender age of 19, when I somehow found my way into a historical reenactment group (the Society for Creative Anachronism, if you must know). I had always been interested in history and I was first drawn to this group because of the historical aspect and, more importantly, because they wore costumes as they went about their anachronistic lives during their weekend events. Who wouldn’t want to pretend to be 13th century French damsel, or maybe a face-powdering, farthingale-wearing Elizabethan woman in the comfort of the 21st century? It obviously isn’t just me! Then I started attending those events and while the appeal of the costumes was still there, the feasts completely seduced me.

The combinations of foods I had never experienced before or even conceived as possible. The many removes (or courses) that made up the meal as a whole. The meats with cinnamon. The pears stewed in wine. I was mesmerized. I wanted more. I wanted, in fact, to be the person in the kitchen, making these dishes straight from history. As someone used to eating only my mom’s home cooking, these were the most foreign and exotic food experiences I had ever had. It just happened that it was food of another time and not just food of another place that opened the culinary floodgates in my life.

Shortly after my first event, I learned that the people who cooked at these gatherings did not invent the recipes out of thin air. No, there were actually cookbooks from the Middle Ages. From Antiquity even! I learned about Sir Kenelme Digbie, about The Forme of Cury, about the Harleian manuscripts, about Apicious. And these people, these kitchen alchemists of the modern age studied those books, researched them, and cooked from them when they seemed to me like little more than random words thrown on a page even when I could read them. It was, to my young and inexperienced self, a revelation and I simply needed to learn more.

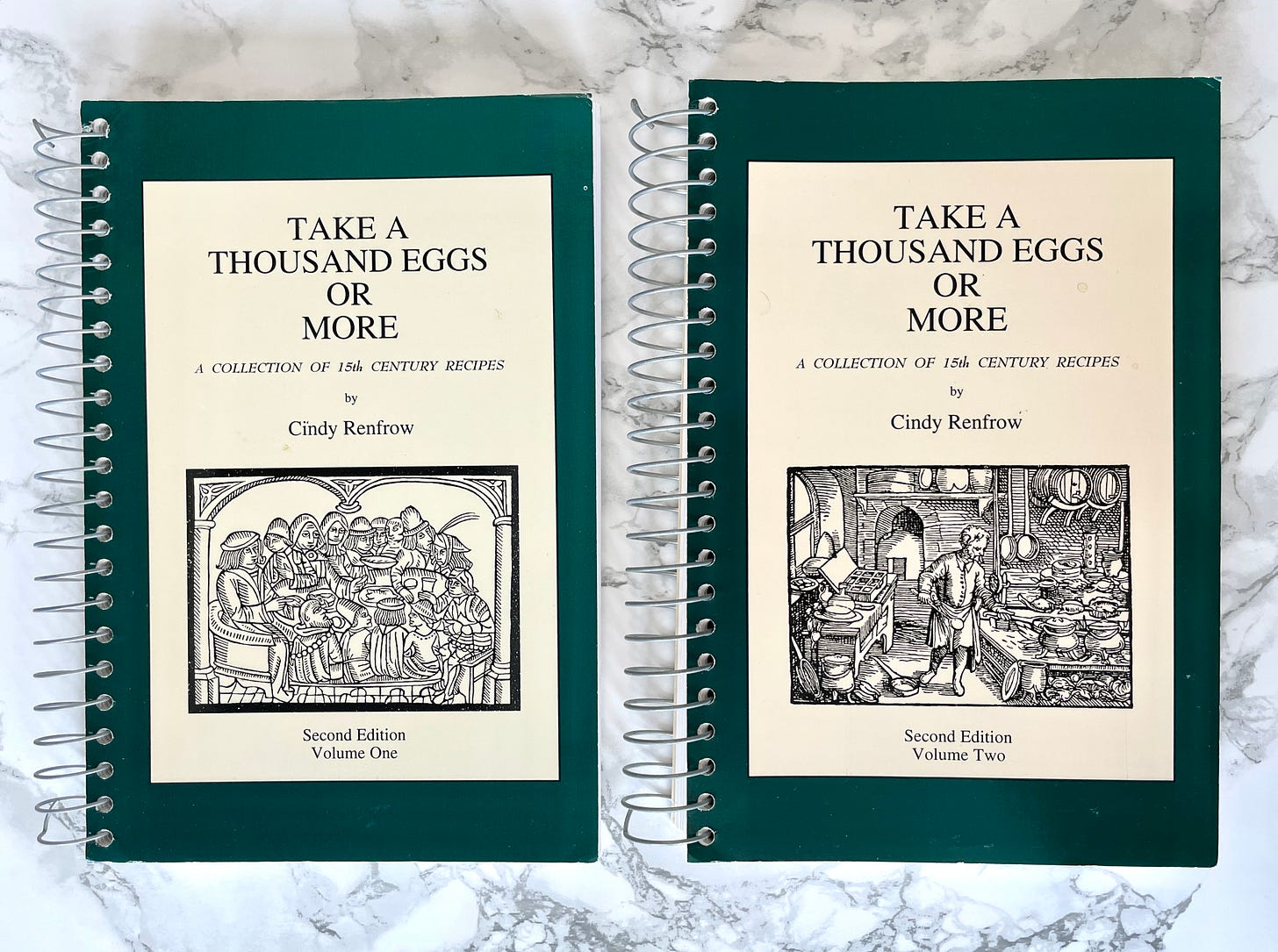

I did not stay in the group long at the time because I went off to the Navy, a story for another day, but I carried that curiosity for historical food with me. One of the first things I did when I left basic training (boot camp) and had access to my own money almost for the first time was buy Take a Thousand Eggs or More. This is a set of two books that use material from several recipe manuscripts from medieval England. The first volume gives the original recipe and a modern adaptation; the second forgoes the adaptation altogether.

I kept buying cookbooks like these and reading them, but I saw no real future in this. At the time, food history was largely culinary history (there IS a difference) and was being done mostly by groups like the SCA, Civil War reenactment groups, and others like them. It was an obscure hobby, an obscure pastime, I thought.

Then, a few years later, I started watching Alton Brown’s Good Eats. As much as I like Brown, he is not the influential party here, it was his nutritional anthropologists. Through their appearances on the show, I learned that people actually made a living studying food and how people cooked and ate in the past. This sparked yet another revelation as I dug deeper: it wasn’t always about the food itself, it was about the cultural, social, and even economic influences food had in society. It wasn’t just about how a dish developed, it was about why, about the external pressures that shaped how dishes came to be the way they are. It was about food in history. It was about how the world shaped the food people ate, and how food shaped the world.

As sheer serendipity would have it, one of my college professors was a food historian. A real-life, living and breathing academic food historian. Not in a TV show, but in my life, in the flesh, just when I had started to think food historians were an urban myth. And even better still, she actively taught food history classes. She gave me the leeway to express myself in ways she hadn’t necessarily planned for. She agreed to let me take the assignments in different directions as I explored, for the first time, food history in earnest. From that class The Pound Cake Project was born and the rest is [food] history. That professor opened the doors to the real-life world of doing food history, she must have seen something worth nurturing in me and I’ll forever be grateful to her.

And so I became a food historian. This is my origin story. Except, it’s not. Not really.

Sure, this is how I started actively working on food and culinary history, but I know, deep in my soul, that the seed was planted much earlier.

I have come to realize that it was not, in fact, the reenacting group or Good Eats that sparked my interest in food and culinary history. It might have been the catalyst, but the chain reaction had already been primed by a childhood in a food-deprived communist country. See, I was born in Cuba and lived there through the worst of the Special Period of the 1990s after the fall of the USSR. The food situation was so dire that, lore goes, cats began to go missing from the streets of Havana. Nothing quite like being deprived of something to make you quite obsessed with it in the long term. My interest in food in society was seeded in the dearth of a Cuban childhood and not in the plenty of an unfamiliar feast in the Modern Middle Ages.

I have written more about my personal struggles with food, memory, and identity. I hope you take a few minutes to read it. It is a deeply personal story that is at the same time nearly universal in its themes among the children of immigrants and immigrant children.

Recipe

For this first newsletter, I want to share a recipe for my favorite Cuban food, Ropa Vieja, shredded beef in tomato sauce that is absolutely worth the time it takes to make. If you want to read more about it, rather than just have the recipe, there is a post on my website. The recipe comes from Nitza Villapol’s 1954 Cocina Criolla. I translated it from Spanish to English and made some necessary tweaks for clarity.

Ropa Vieja

2 lbs beef skirt steak [you may use flank]

1 whole onion

2 whole carrots

1 tsp peppercorns

For the sauce:

1/3 cup of oil

1 onion

2 garlic cloves

1 red bell pepper

1 8oz-can of tomato sauce

1 tsp of salt

1 bay leaf

1/2 cup of dry cooking wine

1 can of pimientos [optional]

Remove as much of the fat and gristle from the beef as you can and place it in a large pot with the onion, carrots, and peppercorns. Cover with plenty of water, enough so that the beef is submerged for the cooking process.

Bring it to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer, uncovered, for an hour and a half to two hours, until the beef is fork tender. Some foam may float to the top during simmering, skim it off as best you can.

When the beef is cooked, remove it from the liquid and place it on a cutting board. Discard the vegetables and peppercorns, strain the broth and save it for another time.

Shred the beef into thin strands.

Slice the onion and the bell pepper. Crush the garlic cloves and cook them in hot oil with the onion, then add the bell pepper and cook them a bit longer. Add the rest of the ingredients [including the beef] and cook, covered, on low heat for 15 or 20 minutes, stirring occasionally so it doesn’t stick. The pimientos can be added chopped up, ground, or can be used for decoration. Serve with white rice and a good fresh salad. Serves 8.

Housekeeping

For now, I plan to write one post per month as I get a feel for regular writing. However, there might be extra posts every now and then if something especially urgent or timely happens in the food world.

Aside from the socials linked above, you can also find me at NYCity Fare on Instagram, where I post photos of the things I eat in NYC restaurants and sometimes when I travel. My love of food is not limited to food of the past! I’m going to Southeast Asia for a few weeks starting this month and I plan to eat a lot and post a lot of food photos!

Loved reading how you came to be a food historian. Need to learn the difference between food/culinary historian. Gonna go watch Alton Brown now. And make this recipe soon. Yum.

Welcome! I enjoyed this.