“What would you not have given for a truffled turkey hen? But in your Earthly Paradise you had no cooks, no fine confectioners! I weep for you!”

I was on Reddit one day, as I often am, when an interesting question popped up on my home feed. On the r/AskFoodHistorians subreddit, someone posted whether anyone knew anything about Auguste Escoffier’s truffled turkey. More precisely, they wanted to know if it was something that was commonly eaten, especially since Escoffier’s recipe, according to the poster, calls for 2 pounds of truffles. They had watched the 2023 film The Taste of Things, set in 1889 with Juliette Binoche (how many French food movies can she be in?!), where one of the characters (Dodin) says “I agree, Grimaud, all conversation must cease when a truffled turkey appears. But this is merely a veal loin with braised lettuce.”

What kind of culinary historian and cookbook enthusiast – not to mention chef-in-training – would I be if I didn’t keep a copy of Auguste Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire (1903) handy? The English translation by M. F. K. Fisher, anyway. I yanked the doorstop of a tome out of the shelf and looked up this truffled turkey. It was, indeed, there. It is recipe 3914, “Dindonneau Truffé,” or truffled young turkey. And while it doesn’t call for 2 pounds of truffles, it does call for 800g, a whopping 1 pound and 9 ounces, give or take. It also calls for 250g – 9 ounces – of raw foie gras.

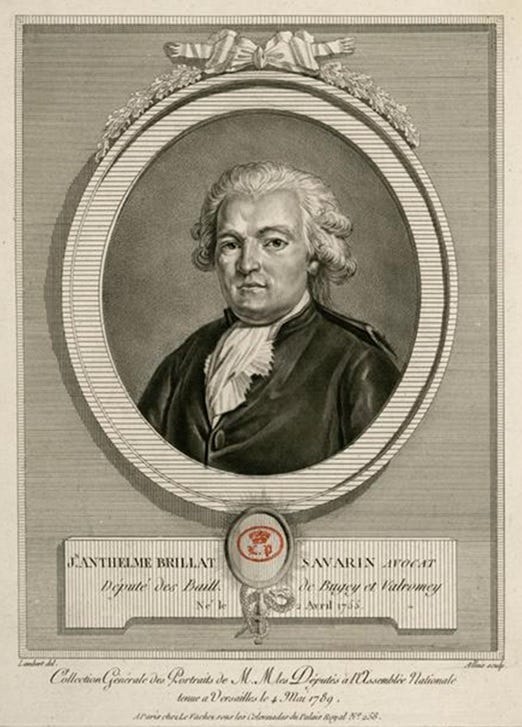

And it had to be a turkey, or at least not a pheasant, as Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin warns in The Physiology of Taste (1825), also translated by M.F.K. Fisher. “A pheasant with truffles,” he says, is not good as one would be apt to think it. The bird is too dry to actuate the tubercle [the truffle], and the scent of the one and the perfume of the other when united neutralize each other – or rather do not suit.” What a waste of your truffles! And your pheasant.

Escoffier disagrees, of course, and offers readers multiple recipes for pheasant with truffles.

Despite his disdain for truffled pheasant, Brillat-Savarin did hold truffles themselves in very high esteem. And, like many modern people, he believed them to be an aphrodisiac across the gender divide. He described them as awakening “erotic and gourmand ideas both in the sex dressed in petticoats and in the bearded portion of humanity.” He was so convinced that truffles’ main attraction was that they excited the senses and arose passions that he gathered a group of male acquaintances into what he calls “a tribunal, a senate, a sanhedrin, an areopagus,” to ponder the statement “the truffle is a positive aphrodisiac, and under certain circumstances makes women kinder, and men more amiable.”

Aside from his rhetoric on sex and senses, Brillat-Savarin also gives us a small glimpse into the contemporary consumption of truffles. He says that around 1780 truffles were very rare in France, and found mostly in small quantities in the kitchens of the Hotel des Americans and the Hotel de Province. “Dindon truffé,” truffled turkey, he explains, “was a luxury only seen at the tables of great nobles and of kept women.” But, by 1825, when he wrote The Physiology of Taste, “the glory of the truffle” was “at its apogee.” He goes on to say “let no one ever confess that he dined where truffles were not.” Truffles had become common, at least in the upper echelons of society, in ways that are foreign to us today, when even the very rich don’t eat truffles as a matter of course.

By the 1920s the lore of the truffle had become so strong that, according to an article published in 1923 by Curtis Gates Lloyd, an American mycologist (truffles are fungi), “many people, particularly Americans and the English” seemed to think that they were “eaten by the French as we [Americans] eat potatoes.” He explains that no, they were not eaten like potatoes, but that, in fact, they were used as flavorings. Lloyd adds that their high cost meant they were out of the reach of ordinary people. Black truffles, he says “in normal conditions before the war [WWI],” were sold in Paris for 10 to 20 francs per kilogram, or $1-$2 per pound. White truffles, on the other hand, were sold at the time of writing for 100 to 400 lires per kilogram, or about $5 to $25 a pound. “At these prices,” he says, “it is needless to say that truffles are not used as food, but as flavoring.” In the span of 100 years, truffles went from the abundance of Brillat-Savarin’s narrative to scarce and expensive, on the way to the outrageous prices of the modern day.

The two World Wars are largely responsible for the decrease in truffle supply, and the increase of their cost, at least in France. Not only did the wars change the physical landscapes where truffles grew, but the movement of people from rural areas to urban areas affected the landscape in other ways. Truffle-growing areas also lost a lot of the knowledge with this migration. Italy and Spain, too, experienced decreased truffle production throughout the 20th century, but not on the same scale as France. The French truffle industry has never recovered, and production today is a speck of dust compared to what it was in the first decade of the 20th century.

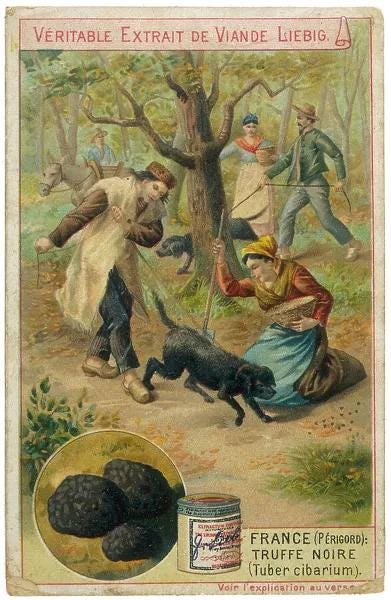

The reason truffles cost so much today is not just because they are scarce but because they are almost impossible to farm. Truffles are mostly wild, and, historically, attempts to plant and cultivate them have been futile. Recently, there has been some more work done on farming truffles, but it’s not easy or cheap. Wild truffles grow underground, and only for a few months of the year. They are difficult to find and require considerable time and labor. To make matters worse, truffles are notoriously quick to spoil. They start to lose their aroma the moment they are pulled from the earth, and last no longer than a week. As a result, shipping them quickly across the world – most truffles are harvested in Spain, France, Italy, and parts of the Pacific Northwest of the US – is expensive, further increasing the cost for the end consumer.

Despite technological advances in other areas, the harvesting of truffles has remained almost unchanged for centuries. The June 1, 1872 issue of Scientific American describes the truffle hunt. People leased land on which truffles grew, and during truffle season, they used small dogs trained to find the fungus. The dogs cost about $20 each, not an insignificant amount at the time. “When the trained dog comes on the scent,” the article says, “the truffle hunter proceeds to hoe up the ground pointed out by the animal as the bed of the truffles.” Pigs were also used in the south of France. Truffle hunters still use dogs and pigs today, and the process is more or less the same.

It should come as no surprise, that, in the 21st century, climate change is the main threat to the truffle industry, including the still-young industry that is farming black truffles (white truffles are still not farmed). Droughts and heatwaves have affected the quality and the quantity of truffle harvests. Truffles need consistent rainfall and moderate temperatures, both of which have been more and more disrupted in recent times. This has been especially a problem in truffle-growing places like Southern Europe, which have gotten hotter. In turn, northern climates like those of Scandinavia and the United Kingdom are starting to become a more serious possibility for the farming of truffles as their winters become milder. The UK’s first harvest of Périgord black truffles, the most prized black truffle variety, took place in March, 2017.

The COVID-19 pandemic, too, had a large and detrimental impact on the nascent truffle farming industry, as well as on traditional wild harvests. The restrictions of movement for the labor force, and some very strict lockdowns, meant that truffle foragers couldn’t harvest truffles in the quantities they had before the pandemic. Supply was low and the added difficulties of transportation and shipping with their many delays and border closures caused a large portion of what was harvested to spoil. Demand was low as well. People weren’t going to restaurants, so restaurants weren’t buying truffles, causing an oversupply in some areas and, again, spoiled truffles. The resulting prices were inconsistent, with prices in areas with oversupply low and prices in areas with undersupply high.

According to some scientists, there might be a silver lining to the effects of the pandemic on truffle harvests. Maybe, the unharvested truffles will enhance biodiversity in the forest. Or, perhaps, the spores from the decomposing truffles will boost future harvests. Experts are still not sure what the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will be on this industry.

Going back to the original question, whether truffled turkeys were really a menu item, the answer is an emphatic “yes.” It comes up often enough in the form of recipes, passing discourse, and other cultural references. According to Alexis Soyer’s 1851 The Modern Housewife, or Ménagère, truffled turkey, or, as he calls it, turkey with truffles, dates to 1720s France, when Guillaume Dubois introduced truffles at his dinners, and the Duke of Orleans gave them to his mistress. This might explain Brillat-Savarin’s comment about truffled turkeys and “kept women.” Brillat-Savarin alone mentions truffled turkey on multiple occasions. In Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery (1892), he is quoted as saying that “in our highest gastronomical societies, when politics are obliged to give way to dissertations on matters of taste, what is desired, what is awaited, what is looked out for at the second course? A truffled turkey.” “In my ‘Secret Memoirs,’” he goes on, “I find sundry notes recording that on many occasions its restorative juice has illumined diplomatic faces of the highest eminence.” In “Varieties XXVII” of The Physiology of Taste, he writes of Adam and Eve “what would you not have given for a truffled turkey hen? But in your Earthly Paradise you had no cooks, no fine confectioners! I weep for you!” Rossini, the Italian composer, is said to have confessed that he had wept three times in his life, one of them being “when, with a boating party, a truffled turkey fell into the water.” In 1894, The Catholic Telegraph described Christmas in Paris, where they said a material sign of the holiday was truffled turkey.

The French phenomenon, given the influence of French cuisine in the United States and the abundance of French chefs, crossed the proverbial pond and jumped straight onto the plates of the American elite. A journal article published in 1876 describing an American independence centennial celebration, lists truffled turkey as part of a meal served. The Epicurean, a cookbook originally published in 1894 by French-born and trained Charles Ranhofer, former chef of New York City’s iconic restaurant Delmonico’s, has a recipe for truffled turkey that puts the opulence of Escoffier’s to shame. It calls not for 1.5 pounds of truffles, not even 2 pounds. It calls for an eyewatering and wallet draining 3 pounds of truffles for an 8-to-10-pound turkey. One ounce short of twice as much as Escoffier’s recipe. This aligns with the immense wealth of Gilded Age robber barons, and how much they could afford to spend. Truffles weren’t cheap in the United States even then.

In Spain, too, truffled turkey, or “pavo trufado,” was a Christmas special. It makes an appearance on the December 1st, 1915 issue of El Gorro Blanco, a monthly culinary magazine published in Madrid. This turkey, of course, had a Spanish flair, with the addition of Jerez sherry, ham, and nutmeg.

Even as late as 1944, truffled turkey was a favorite of some people. Henry Sigerist, a French-born Swiss medical historian at Johns Hopkins University, wrote “a roast turkey prepared in the good old American way with New England stuffing, and served with a cranberry sauce is a great dish, but I prefer my turkey truffled and served with a sauce Périgueux.” He then proceeds to explain his process, and although he does not give us an exact amount of truffles, it looks like he did not skimp. Truffles are sliced and placed between the skin and the flesh of the turkey. More truffles are then added to the stuffing while cooking it, then more truffles – and foie gras – are added after the stuffing is cooled. The entire mixture is placed inside the turkey and the whole thing forgotten, as he says, for two days. During this period, “the meat exposed from all sides to a barrage of truffles, will become impregnated with their delicate flavor.” As if that wasn’t enough, the Périgueux sauce has even more truffles.

Sigerist lamented that, although he used to prepare this truffled turkey often, at the time, there were no truffles. World War II was raging in Europe. The Périgord, he says, where the truffles he used were harvested, was under Nazi occupation. But even if the Allies had “reconquered” it, “the Nazi General Staff would have eaten up the last crop anyway.”

This preparation Sigerist relates is called, according to a 1979 issue of The New York Times, “dindonneau en demi-deuil,” or turkey in half-mourning. It is also truffled, but more subtle than the traditional truffled turkey. They give a full recipe, which they call “Truffled turkey with supreme sauce.” But, alas, it calls for a relatively modest quarter cup of diced black truffles for a 12-pound turkey, a reflection of the cost of truffles at the time. No truffles go in the sauce.

As intriguing as truffled turkey sounds with all the praises, I’m afraid it must remain an indulgence of Ranhofer’s American Gilded Age, of Escoffier’s Belle Époque, or the earlier times when Brillat-Savarin wrote. When the rich were obscenely rich, truffle harvests were large, and the prices hadn’t yet ballooned to what they are today, even if they were never truly cheap. In today’s money, Escoffier’s truffled turkey, which is one of the most modest ones, would cost about $1500 in truffles alone. This is assuming you are using burgundy black truffles, which Brillat-Savarin scorned on account that “they are hard, and are deficient in farinaceous matter.” Farinaceous matter is a substance that has high amounts of starch. Périgord black truffles, of course, cost more. If you want to use white truffles, you are looking at anywhere between $7500 and $12,500, depending on the size of the truffles. Never mind that you’ll cut them up anyway. I got these prices from Eataly in New York City. We can see plainly why truffled turkey, in all its glory, is a relic of the past. Weep for us.

Fascinating story and a recipe I’d never heard of before. I’m curious!

As a side note, we lived in Saudi for many years, and each spring truffle hunting was a big deal! We’d join locals out in the desert, looking for cracked bumps out of which tiny white flowers grew. Although we weren’t as successful as many, we did occasionally come home with a few golf ball -sized truffles! Delicious!